Sixteen years after it was presented at a symposium, Umberto Eco’s paper ‘The Future of the Book’ would seem to be ridiculously out of date and yet, surprisingly, it challenged assumptions and brought up questions that are just as relevant – sometimes more – today as they were then.

Sixteen years after it was presented at a symposium, Umberto Eco’s paper ‘The Future of the Book’ would seem to be ridiculously out of date and yet, surprisingly, it challenged assumptions and brought up questions that are just as relevant – sometimes more – today as they were then.

The text of this paper is online in its entirety at Eco’s Porta Ludovica site and I encourage anyone who is interested in the subject of how online technologies are changing our culture to read it. As academics go, Eco is a very accessible writer. But more than that, it is always good to keep in mind that Eco is an historian, a semiotician and a fiction writer. From all those points of view, how our emerging technologies are changing the way people read, was not only of professional but personal importance to him.

The first criticism of an online environment that he addresses is that it is causing society to become more image and less alphabetically oriented. And he offers an excellent rebuttal. We have always been, says Eco, a visual species. For most of our history, most of the population was illiterate and relied primarily on images for its information. He recall’s us to Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame: one of the characters fears that the invention of the book will be the death of the Cathedral (for Cathedrals were the TV of the Middle Ages). But he also makes another, very valid point: why do be preference learning through text above learning through images? If an interactive educational presentation on the life and work of Chopin communicate the relevant information efficiently, why should we force someone to plow through a ponderous print version of the information and deprive them of the possibility to listen to the music of the composer while they partake of the information both textually and visually? His point is that we need to broaden out our understanding of what literacy is, and use the tools we have to transfer information is the most meaningful and most efficient way possible.

David McCandless offers a good example of how visual language can communicate in more profound ways than text can. Have a look at the lecture: The Beauty of Data Visualization.

Next, Eco tackles the issue of the future of the book from a content perspective, and he makes an important distinction: are we worried that the book will disappear, or that all written text will disappear?

There is no question that for some people, the aesthetic pleasure of holding a book in one’s hands, paging back and forth, lying in the tub, sitting on a sandy beach, can be a delicious experience. However, Eco warns against turning what is, essentially, a sensory indulgence, into an intellectual virtue. He doubts that books will disappear.

Of course this was before the appearance of Kindle and other types of electronic readers. This was before small publishers and individual authors found out that it was possible publish inexpensively and easily if one confined oneself to e-books. Well, we can’t ask him to be prescient in every respect. It might be the case that in future the majority of books may be consumed electronically. And it is valid to ask how reading on a screen might change the reader’s experience of the text. But it is no longer feasible to use the excuse of portability or practicality for why screen reading is implausible.

I’m not dismissing the aesthetic pleasure of cracking a new book open or reveling in the scent of an old one. What I’m underscoring is that this is a romaticization of part of the reading experience. You can read a book on a reader and get just as immersed in the story, absorb just as much information. Let us not confuse the aesthetic pleasure of handling books with the intellectual virtue of consuming their content.

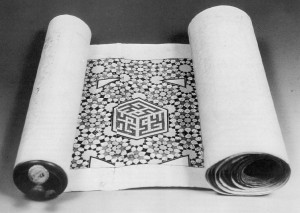

The second part of his question – will all texts disappear – Eco doesn’t really answer. What is says instead is that there are certain types of book-bound information that are much more practically accessed in electronic form. There is no good reason why it is better to have the whole of the Oxford English Dictionary on the shelves of your library. Searchable and saveable electronic text is MUCH more appropriate for this type of text-based information. It is cheaper to reproduce, easier to access, and more convenient when you want to make certain uses of the information. He goes on to talk about how one needs to acquire a certain amount of expertise to use the tools that allow us to read online, and here, I think, in 1994, he probably missed the winds of change. Because even then the push towards usability and plug and play were gaining tremendous momentum. And learning to boot up your laptop and fire up your browser is really not a lot more complicated than grasping the changeover from scroll to bound book.

(I’ll pause here for a comedy break and offer you this lovely piece of video)

Finally Eco goes on to discuss the emergence of a new kind of dialect that has risen with the use of computers. (2B or not 2B). This is especially true with the use of limited space text forms like SMS and twitter. I have heard numerous people bemoan the fact that children will grow up thinking it perfectly acceptable to express themselves in a written form that looks like telegraphic shorthand to us.

Eco’s take on this is that our understanding of what a socially acceptable interchange looks like has varied much through the centuries, that in the 17th century, the opening of a letter to a nobleman might spend the first three pages in what would read to us as nauseatingly over-effusive pandering to the recipient’s ego. Our communication styles are just that, styles. They go in and out of fashion and are culturally dependent. What is important is how the recipient receives the information and with what efficiency. It was expedient in the 17th Century to faun over your correspondent. Today, in email form, it seems almost ridiculous to type ‘Dear John’. Does it make what follows any less or more important/salient/gravitas-laden? He reminds us that we have a curious habit of believing that “the more you say in verbal language, the more profound and perceptive you are” (Eco).

Marousia just wrote a post on an intimately related question: “Musings towards a poetics of social media“.

There is danger of a devaluing of critical awareness in the process of creating content because of the imperative for relevance through the economics of immediacy.

I think my response might be Ecoian: that there have always been people who talk too much, too fast, and think too little, and all social media has done is given them another platform on which to do it. But, on the positive side, there have always been people who want to have deeper, more critical interactions and they’re not going to stop just because social media exists. In fact, social media is simply an enabling platform – for the latest celebrity gossip, or for a musing on the poetics of social media.

I don’t want to summarize Eco’s entire take on hypertext, primarily because it is so good, word for word, you really should read the original. But to say he was intuitive about its possibilities and limitations is an understatement. And I can do no better than to quote his own conclusion to the hypertext part of his essay:

“We are marching toward a more liberated society, in which free creativity will coexist with textual interpretation. I like this. The problem is in saying that we have replaced an old thing with another one; we have both, thank God. TV zapping is an activity that has nothing to do with reading a movie. Italian TV watchers appreciate Blob as a masterpiece in recorded zapping, which invites everybody to freely use TV, but this has nothing to do with the possibility of everyone reading a Hitchcock or a Fellini movie as an independent work of art in itself.”

In the final part of his paper, he attempts to persuade his readers that we have always feared new technologies would eradicate old ones, but in fact they seldom do. They become an addition to rather than a superseding of the mediums we have used before. Not only have new technologies enhanced our choice of communication methods, but have acted to stimulate new and creative ways to use the old ones.

It is in his discussion of community and the formation of the global village that I think Eco failed to see the future clearly. He rubbishes the idea of a global community where people interact with each other. Reading this makes me cringe a little since, at the time he was delivering this paper to the University of San Merino, I was very probably having deeply engaged and certainly filthy cybersex with someone on irc. I guess you can’t blame a professor of semiotics for not having plumbed the depths of cyberspace.

And, although he did not fully foresee the writer/reader relationships that would be possible for me only a few years after he gave this talk, his expectation of the future of the digital environment was essentially positive.

“The new citizen of this new community is free to invent new texts, to annul the traditional notion of authorship, to delete the traditional divisions between author and reader, to transubstantiate into bones and flesh the pallid ideals of Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida...”

And it is in this statement that I credit the man with incredible foresight. Because social media has indeed blown Foucault’s discussion on the author function, Barthe’s theories on authorial control and Derrida’s doubts on our ability to communicate out of the water.

Technology has shown them to be, not the intellectual giants we once thought they were, but dreamers of small dreams.

For me the fundamental change has come at a liminal level. The philosophical skepticism that has dominated the 20th Century is dying and the proof of it is right here. We can communicate, we can understand each other, we can be deeply empathetic and reach across cultures to each other and share deep meaning. And our ability to do this is not dependent on the individual author or reader, but on maintaining an honest, generous and genuine relationship between the two.