There is someone else in the writer-text-reader relationship that is not spoken of much anymore. And it’s sad, because a good editor (I’m using the old sense of the word here) really can make a good book excellent. They can, of course, also make a poor book readable. But when an editor works with a talented writer, wonderful things can happen.

These days, there are very few editors in the old mode left. As publishers began to sell books solely on the writer’s name, not the quality of the work, and as authors have had to take on more and more of a role in marketing their own books, the role of a literary editor has been eclipsed by expedience.

But other forces have also been at work in the demise of the editor. It takes just as much talent and even more skill to be a good editor. A good editor tells you when you have over-written parts of your story. They tell you when you have done something with the protagonist that kicks them out of character and makes them harder to believe. They tell you when what you consider to be the best sentence you have ever written needs to go, because the power of it is killing the rest of the paragraph. Editors see the landscape of literature and smooth out the rough bits. They ‘hear’ the writer’s voice. And the best of them have the rarest talent of all: they can clearly identify the writer’s style and edit a story without eclipsing that unique voice.

Good editors are often not good writers in their own right. If they are, then they tend to push the drafts of a story towards their own voice. It takes someone with an almost blessed ear to make necessary changes to the text without diluting the power of the writer’s style.

Even harder is when a writer and an editor work together on a character’s dialogue to ensure it works, within the context of the character’s voice, and then in the context of the writer’s style. To be able to do that is beyond craft, it’s art.

In a perfect world, editors are not proof-readers. Either because the writer is fully capable of proof-reading themselves (lord knows, I’m not) or because a proof-reader has gone through the work already and cleaned up the spelling and grammar mistakes. But both editors and proof-readers are expensive, and publishers are not willing to pick up the tab, even when they do get to take the cost out of the profits later.

Traditionally, the writer-editor relationship was often a confrontational one. I think that, by necessity, this is as it should be. There is a natural conflict between a writer staying true to his or her vision and an editor whose job is to make the work as perfect as it can be. As one of the commenters on my earlier post said, every editor is going to edit a book differently; as with all art, there are no absolutely right answers. It is the symbiosis between the writer and editor that takes the work from good to fully polished. The trick to surviving the relationship is for both parties to park their egos and dedicate themselves to the text at hand.

I read a lot of sci-fi and fantasy. This is a genre sorely in need of good editors. Books that stretch to 800 pages could have, or should have, been 400. Every writer in the world could benefit from being forced to explain why a 10,000 word side journey away from the central plot is necessary to the story. Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t. But it is a blessing and not a curse that someone knowledgeable compels a writer to defend their rationale. If they can’t, it needs to go. Not because the writer is bad, but because the work is not benefiting from its continued presence.

In a world that is producing more and more written content than ever before in our history, we seem to have killed off a species we desperately need.

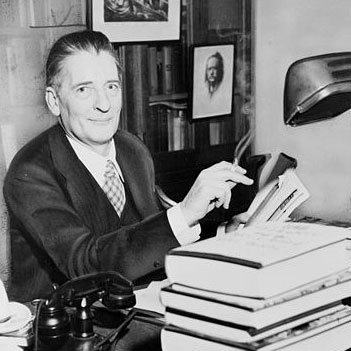

If you’d like to know more about the inimitable Maxwell Perkins, pictured above, there is a very nice article about him in The Independent: The Return of a Man Called Perkins

Really interesting. I so need an editor : (

So do I. So does everyone.

Almost a year ago, I spent all of Christmas Eve/Day reading the private letters and correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald, [ F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew Bruccoli (1994) ] which contained a considerable amount of his exchanges with Perkins. Again, you have put into words what I have been contemplating in the months since. His influence and guidance is clearly evident in their correspondence. I secretly have wished to find an editor to help me, the way Perkins helped Fitzgerald. But yes, you are correct, in suggesting how the editor has become an endangered, if not extinct species; replaced by agents, publishing houses, copy-write editors and many writers working independently by necessity. Most recently, I suggested the value of the editor as paramount to a discussion about the value of an agent for a playwright. The responses I received were indicative of the veracity of your conclusion. Many do not even realize how the definition of “Editor” has changed in the last 50 years. And worse, the new definition provokes a negative connotation for many writers, who consequently dismiss the idea–to their loss. And to ours, as readers. Excellent post, again, RG.

Once upon a time, I thought I might want to be an editor. My reasoning was: I like reading, I like writing, I can spell, I can use grammar correctly etc etc. But I realised, as explained in your post above, RG, that these are just the nuts and bolts of proof reading, and that I do not have that editing gift of being able to see the text in the round and make suggestions about where it is going off course.

So I became an accountant instead. 🙂

Well, I don’t think it is something you start off with. I think, like anything else, it requires a lot of doing and practice.

I completely and utterly agree with you.

(And a good editor would probably have told me to lose either ‘completely’ or ‘utterly’ there.)

snicker

I think I might have made a good editor. If I could get past worrying about hurting people’s feelings. I think I’m better at editing other people’s stuff than my own. I have too much attachment to the things I write. Interesting post. Thanks RG.

I think, once you commit yourself to making the piece of work you are editing your priority, the fear of hurting feelings tends to fade. And everyone is better at editing other people’s stuff. Writers are always emotionally invested in their work. It’s natural.

Thank you for writing this post!

I couldn’t imagine feeling I didn’t need an editor, and yet I constantly deal with people who want to be published, but feel the editorial process is pointless.

To make it as a writer, one has to be a bit of a masochist, especially in the earlier stages. Writers should want their work to be undressed, pulled apart, yanked open, and ripped into. Writers need to want to hear every single thing they’ve done wrong, so that they can learn to make it better.

And that masochism shouldn’t cease upon one’s first “real” publication, or upon “making it.” I wait with bated breath for my editorial letters, or my critique letters form my beta readers and critique partners. I can’t wait to hear what I’ve done poorly, or what is confusing, or what simply doesn’t work…because then I can fix it.

The act of writing is actually about a third of the process that is writing, and people have to be willing to engage fully with the other two-thirds of the process (the stripping, the painful revelation of weakness, and the building back up) to be real authors.

“I can’t wait to hear what I’ve done poorly, or what is confusing, or what simply doesn’t work…because then I can fix it.”

The point you’ve made here is an important one. And it’s a real hurdle for newbie writers. You need to have a fair amount of confidence in your skills and ability to ‘fix it’ in order to really appreciate an editor’s negative feedback. And this can make for a bit of a vicious circle when you’re just starting out.

Great post, and so true. There’s nothing like the synergy between two brains that are both striving to make a work the best it can be. The first time I ever (successfully) worked on a piece of writing “with” someone was in college, when I co-wrote an essay on The Picture of Dorian Gray with a classmate. I was amazed at how much better we were together. As you pointed out, some antagonism was necessary, but the best part was how we pushed each other’s ideas to the next level. I hope that if/when I have an editor for my fiction, I’ll have the same kind of “Yes! Why didn’t I think of that!” intellectual relationship.

I have been working with a writer since the beginning of September. Initially, I was just a glorified proof reader with the occasional question about tense or word choice. He is extremely prolific and I have worked on his words almost every day.

He has tought me so much about being a good writer but even more about being a good editor. I find myself struggling to write creative prose more and more. Yet, at the same time, I am becoming more familiar with his style, his voice, and comfortable challenging him to do his best. I have hardly written two words in the past month. Yet, if I have to go more than two days without something new from him to read and work on I start to twitch.

Reading this piece of yours makes me feel that maybe it’s okay if I’m not a writer of fiction. I have a feeling I wasn’t cut out for that. You have also made me feel very proud to say that I am an editor (and definitely in the old style) of the tremendously talented Keith Dugger.

Congrats! You’ve joined a very hallowed club.

Part of the reason people assume that editors are proofreaders is the confusion over the difference between a copy editor (who checks grammar and spelling and formatting consistency and a dozen other things) and a developmental editor or manuscript editor, who works with the content and style. Of course there is some overlap, especially with grammar.

I think the best-looking books have both types. The development editor works with the manuscript first, and when the content is finalized, a copy editor checks it for correctness. Apparently you are right that in some areas of fiction, a book might not get both–or even one! Fortunately this change hasn’t hit my niche of non-fiction.

I both write and edit, and I can tell you, it’s damn hard to edit your own writing. Writing and editing are different skills, and you look at the text in a different way. I like to think that being an editor makes me a better writer, and that being a writer makes me a better editor, but no matter how clean a manuscript I have thought I was submitting, I have been ever so grateful for the work my editors have done for me! I still remember the first time I was edited; I was practically in shock that a publisher would provide such a service to me, and for free.

I’m not sure I agree with you on the relationship being a contentious one. I prefer the attitude that both parties are working on the manuscript, which is a separate thing. Where the editor attempts to work on the author’s ego there are rarely good results. Both parties have the same goal–to make the best book possible–though they use different skills to get there.

These days when I take freelance editing projects for publishers one of my first questions is how easy the author is to work with–by which I mean, is the author willing to change anything. I can work with all types, but it’s a far easier thing with someone who’s willing to look at the text as something that can change if necessary.