Thinking about the metanarrative possibilities of the Happily Ever After trope, it has occured to me, in re-reading Foucault’s “What is an Author?” that there is a kernel of something here to be explored.

Thinking about the metanarrative possibilities of the Happily Ever After trope, it has occured to me, in re-reading Foucault’s “What is an Author?” that there is a kernel of something here to be explored.

In examining the relationship between writing and death, Foucault gives us two examples: the hero in the Greek epic and case of death postponed in 1001 Arabian nights.

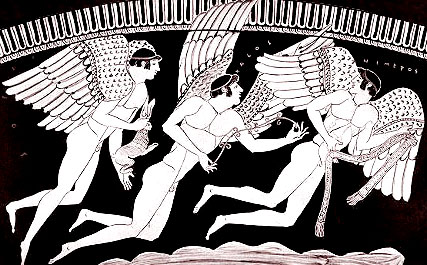

In the Greek epic, the hero must die a young death in order to be immortalized. Not just immortalized within the boundaries of the story, but beyond it. It is, in a way, as if his death buys his passage out the confines of the fictional text, out the back cover of the book and into our collective cultural landscape. It’s a very religious notion. He dies in the text so that he can be resurrected to a sort of immortality in the real world.

Perhaps in this same way, the ‘happily ever after’ ending serves as a similar veil between the fiction and the world. Does it allow for the the essence of romance, always new, always in a state of desiring, always at that glorious point of consumation, of ‘I love you’ to be captured in amber, survive the ending of the fiction, and escape, as an ideal into the real world?

In the second example he gives, 1001 stories are told in an effort to forestall death: “to postpone the moment of reckoning that would silence the narrator.” If we accept that, in the reading, the reader becomes author, then perhaps the ‘happily after ending’ is, in a way, the stopper of the clock. Perhaps it allows the reader to continue on, after the fiction is over, narrating the height of the romantic moment forever.

Just musing. Hehe. Had to write it down somewhere.

Ooooh, yes. I think you have something here!

I think you’ve hit the nail on the head at the nature of all creative endeavor, especially for the reader or viewer, whose imagination becomes the home (and only real security) for the created.

I think it was in Sam Shepherd’s play Fool for Love, there’s a line from the Old Man, something about a woman he loved, but never told – because to tell her would have ruined it. The fantasy of his love for her was easier to deal with, more satisfying.

Isn’t that imagination all over?

Not only that, but it very succinctly describes most of my love affairs.

It must speak for most of us, actually. I’m not sure I’ve ever told anyone my real feelings. Rejection isn’t particularly romantic. Or is it? There’s another post for you – the psychological dependencies of the perpetually, purposefully unloved.